Awareness Week 2018: Q&A with Kenny

Early years for children born with a cleft come with three main issues – hearing, teeth, and speech.

Many children with a cleft palate have recurring ‘glue ear‘, meaning they need hearing aids or grommets. If this isn’t recognised and properly treated, they can have problems with language development, and later on in school with taking part in lessons. Read more about hearing.

If a cleft affects a child’s gums, teeth often come through twisted or in the wrong place, and keeping them clean is extra hard. Healthy teeth and gums are important for everyone, but they’re especially vital for anyone hoping to have further surgery or orthodontic treatment. That’s why it’s so important for parents to make their child’s oral health a priority. Read more about dental health.

The soft palate (the roof of your mouth towards the back of your throat) is used to block off air from the nose while making certain sounds like ‘m’ and ‘n’. A cleft palate can change how this works, even after surgery. Around half of all children with a cleft lip and palate will need some form of speech and language therapy to make sure they can be easily understood by their peers by the time they start school. Of these, the latest figures from CRANE show 60% achieve ‘normal’ speech by the time they’re five years old. The rest will need ongoing speech and language therapy or even further surgery to help them be clearly understood. Read more about speech.

Having clear speech that others can easily understand is something most people take for granted. ‘Good communication skills’ are an essential part of many jobs, and often ‘articulate’ is used as another way of saying ‘intelligent’. So when someone sounds different, it’s all too easy for others to dismiss them, or to respond in a way that just makes things worse.

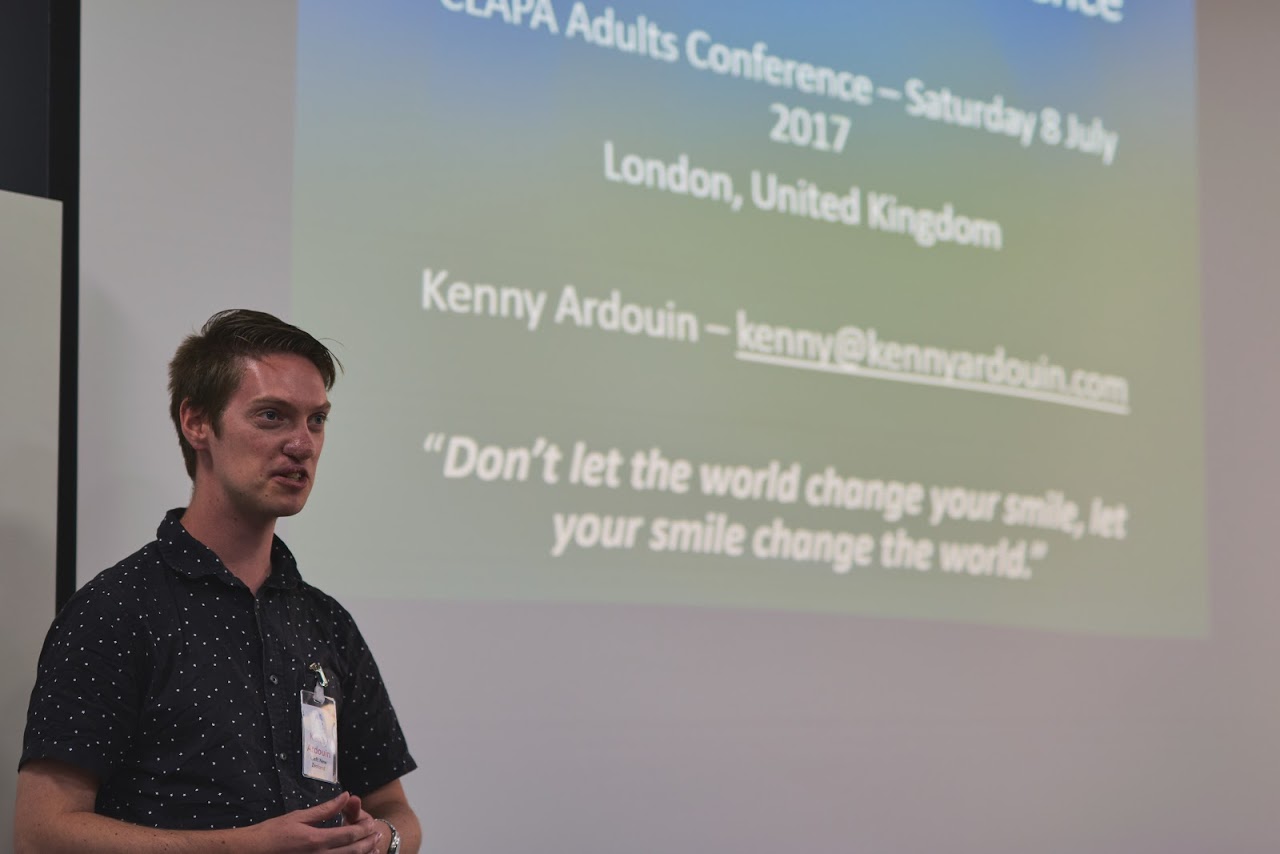

Kenny Ardouin joined CLAPA in March 2018 to kick off our Adult Services Project. He brings a wealth of experience to CLAPA – as well as being born with a cleft lip and palate himself, Kenny is the former CEO of Cleft New Zealand, and is a trained Speech and Language Therapist.

For Awareness Week 2018, we sat down with Kenny to ask about his experiences as a speech and language therapist, and how being born with a cleft changed his perspective.

How did you become involved with speech and language therapy in the first place?

I kind of fell into it in a way. I was thinking of ways I could use my experiences that I’ve had to help other people. I was looking back at my own cleft journey and for me there were sort of two professionals that stood out – speech and language therapy and orthodontics – in terms of having made a big difference to me (it’s worth noting, I unfortunately didn’t have access to psychology because I’m sure they play a tremendously positive role for a lot of people).

I felt that, of all the specialists I saw, those were the two that above all else saw me as a person. I was a person first, rather than a patient and I really liked that sort of mentality.

Looking back at my own experiences, having had a lot of speech therapy myself, I can see the benefit that that’s had for me in being able to communicate and feel much more confident about myself. It’s not until you can’t do these things that you really realise how much the general population kind of take that for granted and I wanted to be able to help other people to find their voice as well.

What would be a typical day for you when you were working as a Speech and Language Therapist?

My typical days were quite varied because I was in the unique position of being able to see people right across the lifespan. The sorts of people that I would see were people with extremely complex communication needs, so it wouldn’t be a case of seeing a child who can’t make one particular sound, it was more people who really couldn’t be understood.

I could be working with a child in the morning who was born with a condition such as a cleft or cerebral palsy, then in the afternoon I might be seeing an adult who’d had a stroke. Obviously, they’re very different in the sense that the child has never had speech, which is very different to someone who has had speech, has known exactly what it’s like and is suddenly in this position of losing it.

That is often the case with people with cleft as well. You know what you want to say, you just can’t get the words out. The best way I can describe this to other people who haven’t experienced this is that it’s like going to another country where people speak a different language. You know exactly what you want to say, you’re an intelligent, smart person, but in that particular environment you cannot express yourself and be understood. It’s incredibly, incredibly frustrating and leads to people making assumptions about your capabilities as well, which is unfair.

What would you say were the hardest parts of your role?

Well, there’s two really hard parts. I would say probably the hardest part was working with people really extensively with for a long, long time and for whatever reason their speech just doesn’t improve. That’s the case sometimes. It’s often not something that just speech therapy alone can do. We see that often with cleft, that you’ll need surgeries to go along side the therapy to actually get the best speech outcome.

The other hard thing that I found as well, with working with adults who have had strokes and other life-threatening things like that, is obviously that you might lose patients because of their health while they were still in your care for their speech. You’d build up a rapport as you would with anybody else, and I think for professionals in that situation often you’re in a strange place, because you’re not part of their friend network or their family network but you’ve obviously spent a lot of time with them.

What were the most rewarding parts of your role as a Speech and Language Therapist?

The rewarding parts are when you really make a breakthrough and when you see someone not only now physically be able to communicate, whether that be through speech or another method that works for them, but also with the confidence that comes with that. You can see their higher self-esteem that goes along with that. For me, it’s not just what they can do in the clinic but when you casually catch them as you’re walking into clinic talking or communicating out in the waiting room or out in the playground. For me, that’s when I actually know that this has all been worthwhile.

What advice would you give someone, a child or an adult who’s been referred later to their cleft team’s speech and language therapy service, as they begin their treatment?

The first thing to know is that everybody is super friendly. It’s a really caring and compassionate field and there’s nothing to be afraid of. There’s nothing that speech therapy will do that will hurt you! Also, to just stick with it because I think it’s at the point where you feel like you’ve tried everything, you’ve been at it for a long time, when you’ll eventually start to make headway and make that breakthrough. It does take a long time and you’ve got to do your bit at home as well.

Unfortunately, just seeing a speech therapist for an hour a week is not enough. You need to go home and practice. There are so many different ways to do that, you can play games, you can read books. My biggest message to parents, always, is read to your children. If there’s one thing that you can do for them to improve their speech and language, it’s read. Read to them as much as you can. When you think about how we pick up language, no one explicitly actually tells us what to do, it’s just that we soak it up. By reading to your children you’re exposing them to new vocabulary but also you’re showing them in the book how the spoken form of a word matches to the written form of a word which is essential for them to be able to read and write later on.

How does your previous role as a Speech and Language Therapist impact the work you’re doing now as CLAPA’s Adult Services Coordinator?

It’s been incredibly helpful to have that background as a health professional. I think it really helps bridge the gap between some of the support group network and the professional network. The thing that’s always struck me, because I’ve always been in the unique position of having been a patient and a health professional, is that we’re up against the same battles. Things that really frustrate you as a patient are the same things that frustrate a health professional (whether they’re at liberty to say it or not is another thing). They are doing the best they can with the resources they’ve got. Obviously it will take combined effort and advocacy, and it could well be it takes bigger organisations such as government, to provide better resources. We really are all on the same team.