Speech

Around half of all children with a cleft palate will need some form of speech and language therapy (SLT). This page explains how a cleft can affect speech, what treatment is available, and what to do if you can't get the SLT your child needs.

One in ten children (with or without a cleft!) have Speech, Language and Communication Needs (SLCN), meaning around three children in every classroom will have issues that make communicating with others difficult. This can include having trouble knowing how to talk and listen to others, understanding words and instructions, or having speech which is difficult to understand.

SLCN can sometimes be a hidden problem, because these children look just like others and can be just as clever. But communication problems can affect children in a variety of ways which may not be obvious at first. What is seen as ‘bad behaviour’ or problems with socialising with other children could just be children attempting to communicate or becoming frustrated at not being understood. Speech also helps us understand and develop language, so problems with speech can mean children struggle to read and write.

These problems can often be missed or misdiagnosed, but thankfully the treatment pathway for children with a cleft includes speech and language assessments to ensure that any issues with speech are identified and managed early on.

Jump to:

What does Speech and Language Therapy Involve?

What you can do at home to help

Problems with accessing Speech and Language Therapy

How a cleft affects speech

A cleft palate can affect speech and communication abilities in different ways. There is huge variation in how children with a cleft develop in terms of speech, and the severity of their cleft is not always a good indication. Often, it won’t be clear how a child will be affected until they start to speak.

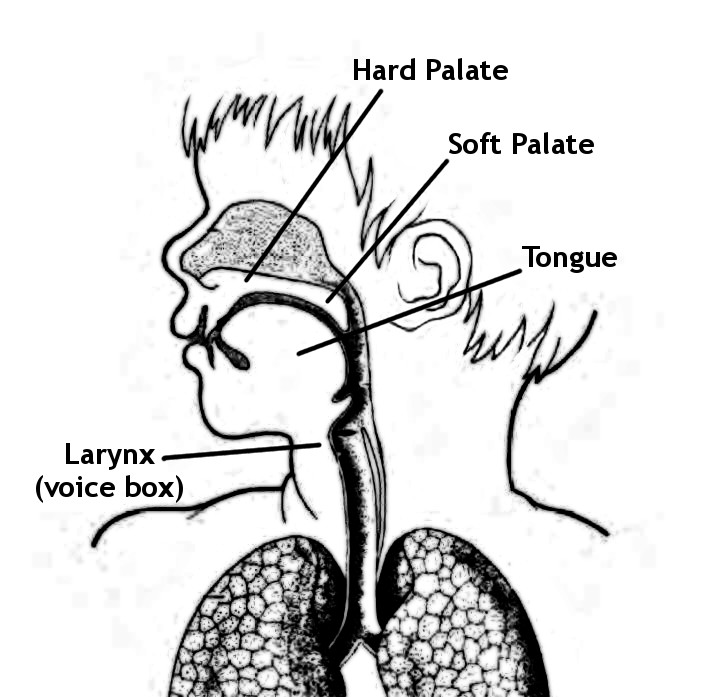

Children with a cleft that affects their soft palate (the part towards the back of the throat) may have problems with speech that include sounding nasal. This is caused by the soft palate not being able to properly close off the mouth from the nose while speaking and therefore letting air escape through the nose. This is known as velopharyngeal impairment (VPI). Additionally, if there are still holes (fistulas) in the palate, this makes it difficult to make some consonant sounds such as s, z, sh which require placing the tongue there to make the sound. If teeth are missing or not in the right place, some dental sounds such as f and v may be more difficult to articulate.

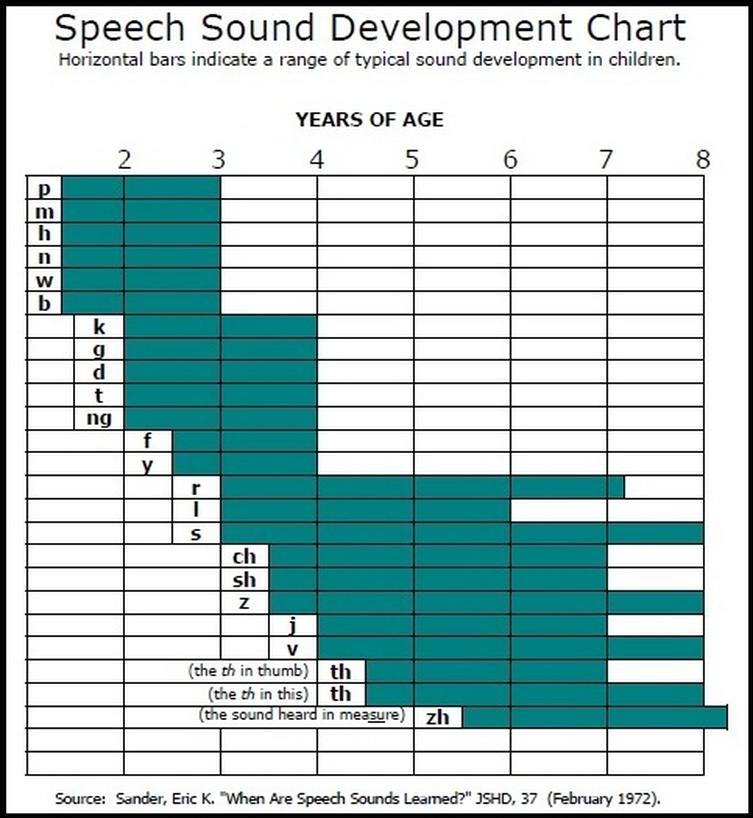

Children will start to learn how to make different sounds as they grow up. The below graph illustrates what sounds children (with or without a cleft palate) will start to develop at different ages.

Speech issues may be something that parents only notice as their child grows up. It could be that while you can understand your child just fine, others have more difficulty. This isn’t such an issue when they are still very young, but it needs to be treated if they are to start school and interact with others confidently.

Sometimes, a child’s speech problems can be made worse by (or be the result of) hearing issues, as they can’t hear themselves speak, or hear other people modelling the correct pronunciation of the words, and so can’t work to fix the problems themselves.

Around half of all children with a cleft palate will need Speech and Language Therapy (SLT) at some point, and any speech issues your child has should be picked up and managed by the Cleft Team early on. Your child will have an assessment at around 18-24 months old, and another one at 3 years. In both cases, treatment will be recommended if they think it is necessary.

It’s much less likely for children with a cleft lip to have problems with their speech, but if this is something you are concerned about then do talk to your Cleft Team about it.

The aim is for children to have good quality, intelligible (understandable) speech by age 5-6 so that they can enter school able to participate fully in class and communicate with their peers.

Many children will only need SLT when they are younger, but some will need support into their teenage years. How much, and how this is delivered, will depend on the needs of the child in question – talk to your Speech and Language Therapist if you have concerns.

Some children may need additional surgery to reduce the amount of air escaping through their nose when they speak. This is called secondary speech surgery and there are a number of procedures used such as a ‘pharyngeal flap’ or ‘pharyngoplasty’.

Cuts to the NHS have put some local SLT services in jeopardy, meaning you may not be able to get the treatment you need for your child at a local level. Find out what you can do about it.

What does Speech and Language Therapy Involve?

A speech and language therapist (SLT) will usually carry out an initial assessment at around 18-24 months, followed by a further assessment once the child is around three years old. These assessments look at how well your child understands words as well as how they sound when they speak. In these sessions it may seem like the therapist is just playing games with your child, but this is an important part of the assessment process to be able to assess the child in a more natural activity.

If the assessments show that a child has difficulties with speech, the SLT will advise on further treatment, which, as well as direct therapy, could include teaching you exercises to help your child’s development at home and/or liaising with your child’s teachers to make sure they get appropriate support outside of any scheduled SLT sessions.

The SLT will work with your child for as long as they need help. The aim is for all children to have good quality, intelligible speech by the time they start school.

Sometimes, children with a submucous cleft palate will not be identified until they are seen by their local SLT, GP or other medical professional for unexplained speech issues. Those children will then be referred to their local cleft team and assessed to see what kind of treatment, including surgery, may be necessary. In some cases, children will get therapy for hypernasal speech and a submucous cleft palate can remain undiagnosed for many years, which is one reason why awareness of all kinds of clefts is so important.

Videofluoroscopy

As some speech problems will be caused by your child’s palate, it’s important for the SLT to see how well this is working. They might do this using a videofluoroscopy, which is an x-ray taken while your child is talking (see the video below), or by using other special equipment such as a nasometer, which measures the amount of air coming out of the nose compared to the amount of air coming out of the mouth during speech. Sometimes, a nasendoscopy may also be needed, which involves passing a very narrow tube, attached to a video camera, into your child’s nostril.

What Happens When I Come for my Videofluoroscopy? from CLAPA Video on Vimeo.

What you can do at home to help

Encouraging speech and language development is important for all children, not just those with noticeably different speech, and so here we’ve collected together some basic tips on what you can do at home.

Input Modelling: This video describes ‘input modelling’, which is a way to help younger children learn sounds by encouraging them to watch you making these sounds.

Visit the South West Cleft Service website for a list of useful videos and resources to help you support your child’s speech therapy at home.

The South Wales Cleft Team have put together the above video to show what’s possible using just a few basic items and toys. The Cleft Team are keen to hear your thoughts on the video, so if you watch it please take a few moments to fill in the feedback questionnaire for parents and carers.

Please Note: Babble Bags are no longer available from CLAPA, but the items are readily and cheaply available in shops should you wish to put together your own.

More Practical Tips:

- From an early age, encourage your child to make certain sounds when they babble, especially sounds like p, b, t and d. Make sure they can see your mouth and lips as you make these noises.

- As your child grows up and starts talking, use words they know in games and songs to help them practice certain sounds, e.g. ‘baa baa black sheep’ for b.

- Play games or sing songs with your child that encourages them to blow air through their mouths rather than through their nose, such as these songs developed by the team at Spires Cleft Centre.

- Talk to your child whenever you play together. Use short sentences and repeat keywords, and encourage them to watch your mouth and lips as you speak.

- When your child tries to communicate with you, repeat back correctly the sounds and words that they say, but don’t tell them they’ve done something wrong or ‘over-correct’ them as this might make them feel anxious about talking in the future. You can also help with their language development by copying your child’s words in your reply so they understand how these words fit together. For example, if your child is trying to say ‘daddy’ but can’t pronounce the ‘d’ sound, use the word correctly in your reply, e.g. ‘yes, daddy is over there.’

- Be patient if your child can’t make new sounds yet – this takes time for every child, not just those with a cleft!

- Give your child chances to talk. Try not to anticipate what they might say, finish their sentences or tell them to say certain words, as this might discourage them from talking or make them feel under pressure. However, when they have finished speaking, do expand upon what they have said – for example, if your child says “daddy car”, you could respond with “Yes, that is daddy’s car.”

- For some children, they won’t be able to physically make certain sounds, so if you don’t see any progress then talk with your speech therapist, it could just be that your child needs further surgery or a different kind of treatment to move forward. Avoid persisting with having the child attempt a sound which they cannot make.

- It’s important that your child feels positive about their speech and language development, so remember to be encouraging and to celebrate their successes! When your child reaches a milestone or says a certain word or sound correctly, give them specific praise so they understand what they did right, and encourage them to repeat it.

More Resources

BBC Tiny Happy People – Activities for babies, toddlers and children aimed at improving communication skills.

Resources from the South West Cleft Service

Speech At Home – Parent-led speech therapy courses and resources, due for launch in Summer 2021.

Surgery

“I suppose I was so focused on his surgery and lip repair the thought of any problems with his speech didn’t occur to me. When Joe was four his speech really hadn’t improved and he also had a lot of air escaping down his nose when he tried to pronounce certain sounds. Joe was offered further surgery to help close the gap, we agonised over this as he had had 2 major operations already and we couldn’t guarantee the operation would improve his speech. We went ahead with the operation and am pleased to say the improvement in Joe’s speech was nothing short of a miracle. We noticed the difference within a few weeks and now 3 years on Joe’s speech is almost perfect. Yes he still has a few problems with certain sounds but his vocabulary is wider and his confidence has grown.”

– Judith

Surgery will only be offered if the Cleft Team feel it will help your child in a way that isn’t possible through SLT alone. Every child is different, so what can be a huge boost for some can make little difference to others. It’s important to talk to your Cleft Team about any concerns you have, and to make a decision which is right for you and your family.

Surgery to improve speech can be done later in life, but it can be easier if it happens while your child is still young, as not only is it less disruptive to their lives, but it means that they won’t have to re-learn how to talk after surgery as they will still be learning anyway.

Your child will be thoroughly assessed by the SLT and surgeon before and after any surgery to ensure any changes in their speech are managed.

There are a number of different surgeries to help reduce the amount of air that escapes through the nose when talking. They include pharyngeal flap, buccinator flap, pharyngoplasty, and a palate re-repair surgery.

What happens?

Pharyngeal Flap: A square flap is taken from the lining at the back of the throat and attached at one end to the soft palate.

Buccinator Flap: Part of the inside lining of the cheek is moved to make the soft palate longer.

Pharyngoplasty: Two pieces are taken from the sides of the throat and joined together to make a ‘bulge’ on the back or sides of the throat.

Palate re-repair: The original cleft palate repair is opened, the muscles are realigned, and the palate is repaired once more.

These procedures help to block excess air from going into the nose, but still allow normal breathing. As with cleft repair surgery, your child will be asleep the whole time and will usually need 1-2 days in the hospital afterwards before being sent home. They’ll need a soft diet for 2-3 weeks, and your Team will give you other recommendations to follow. The inside of their mouths will be swollen after surgery and it will take a while before you’ll be able to tell clearly if there has been any change in their voice – how long depends on the procedure.

Problems with accessing Speech and Language Therapy

When the current Cleft Team system was set up around 15 years ago as part of the centralisation of cleft services, it was intended to work using a ‘hub and spoke’ model where the Cleft Units are central specialist hubs, and local health services provide care closer to home in consultation with the specialists. Often, children with a cleft are assessed by a specialist in their Cleft Team, who then recommends further treatment by local service providers. The cleft specialist will help to advise these local service providers on what help the child needs.

This is how Speech and Language Therapy for cleft typically works – a child is assessed by the specialist SLT with the Cleft Team, and if further treatment is needed you will be referred to a local service provider who will then, ideally, work with the Cleft Team to deliver your child’s care. However, cuts to NHS services mean that this isn’t always the case, and in a 2015 survey run by CLAPA, only 55% of parents accessing Speech and Language Therapy said their child got everything they needed.

Although this is a problem that varies from area to area, it isn’t about the Cleft Teams – it’s about local services, and differences here can be down to postcodes, not just counties or wider areas.

If your child needs SLT, you might find that after being referred to a local treatment provider, your child has not been given appointments within the recommended 18 weeks and has instead been put on a waiting list.

Why might my child be on a waiting list?

This is, unfortunately, something of a lottery. Some areas of the UK are able to provide SLT services to children almost immediately after a referral. Others have to put children on long waiting lists or may not be able to see them at all.

This sometimes depends on how urgent the need for SLT is judged to be. Naturally, children whose speech is completely unintelligible, or children who are nonverbal (such as some children with autism spectrum disorders), will be a higher priority for treatment than children who might only have problems pronouncing certain sounds.

In some areas, local SLT services are simply overstretched and cannot accommodate all the referrals being made, even if the need is urgent. You should be able to find out what place your child has on the waiting list and how long they can expect to wait by asking your local SLT service.

If your child is on a waiting list or you have been told they cannot receive any care, and you think this will badly affect their development, you can make a case for your child by following the NHS’s complaints procedure.

It may help for you to talk to your Cleft Team and inform them that you haven’t been able to get treatment locally. They may be able to refer you elsewhere, or at the very least they should be able to give you a report of their recommendations. This will help if you choose to take things any further, as it is proof that your child needs treatment they are not getting. In some cases, they may be able to help you with the wording of your complaint and make it more effective.

If you want to make a complaint, it’s best to do it as soon as you realise there is a problem, or at least within 12 months. To help you get started, check out the Citizen’s Advice Bureau’s page on complaining to the NHS and also writing a letter of complaint.

Remember to keep records of all letters and emails that you send and receive, and keep a note of times, dates and anything discussed over the phone.

Even though this might be an emotional issue for you, try to write your complaint out in a detached way that explains your problem, provides evidence, and lays out the solution or outcome you’re hoping for, even if this outcome is just a proper explanation of why this has happened.

Write to the SLT Provider: Make a case for your child by writing to your local SLT provider and explaining why your child is entitled to treatment. If you don’t know who your local SLT provider is, contact your local Clinical Commissioning Group (previously called Primary Care Trusts) and ask for information on who you should speak to.

Every NHS organisation has a complaints procedure, though this differs from place to place. If you can’t access the complaints procedure on the website of your local service, ask for a copy in person or over the phone, and it will explain how you can take things further.

It can be a good idea to speak to the service provider directly over the phone or in person, as they may be able to address your concerns (or at least give you a satisfactory explanation) without you having to go through the complaints procedure. This is called a ‘local resolution’. However, if you don’t feel comfortable doing this, or if you tried and your problem wasn’t resolved, you can still follow the complaints procedure.

Other Options

Go through PALS (Patient Advice and Liaison Service): Your local hospital or service provider should have a PALS Office where you can talk about any issues you’re having and seek advice. You can find a list of PALS offices on the NHS Choices website. PALS can also put you in touch with the NHS Complaints Independent Advocacy Service which supports people who want to make a complaint.

Citizens Advice Bureau: This service provides practical advice for all sorts of issues, from claiming benefits to complaining about a poor service. They can advise you if there are any other courses of action you can take, and can help you understand what the law says about your situation. They also have a number of template letters you can use for all sorts of different situations on their website.

Ask that your child be given an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP), or an Individualised Educational Programme (IEP) in Scotland: While we don’t class having a cleft as a disability, it could be that your child’s speech is affected enough for them not to be able to participate in school like other children. Your child’s school may have the resources to have a local SLT visit the school and work with a number of patients at a time, or just with your child. They may also be able to advise on how best to access these services outside of school, for example getting a statement of special educational needs for your child. Children with a statement of SEN or an IEP may be seen faster, and in some areas with oversubscribed SLT services this may be the only way to get seen by a local provider.